Inside the Vet World Part II: Dr Sam on Passion, Perseverance and the Changing Face of Pet Care

Munirah Ahmad Niza

October 16, 2025

Dr Sam shares his journey of resilience, compassion and what it truly means to be a vet in today’s fast-evolving pet care industry.

- Vet school taught him independence, accountability, and the importance of self-management.

- His career path spanned government service, sales, and farm work before finding his place in small animal clinical practice.

- Success in veterinary medicine isn’t just about medical skills — communication, business sense, and self-awareness matter too.

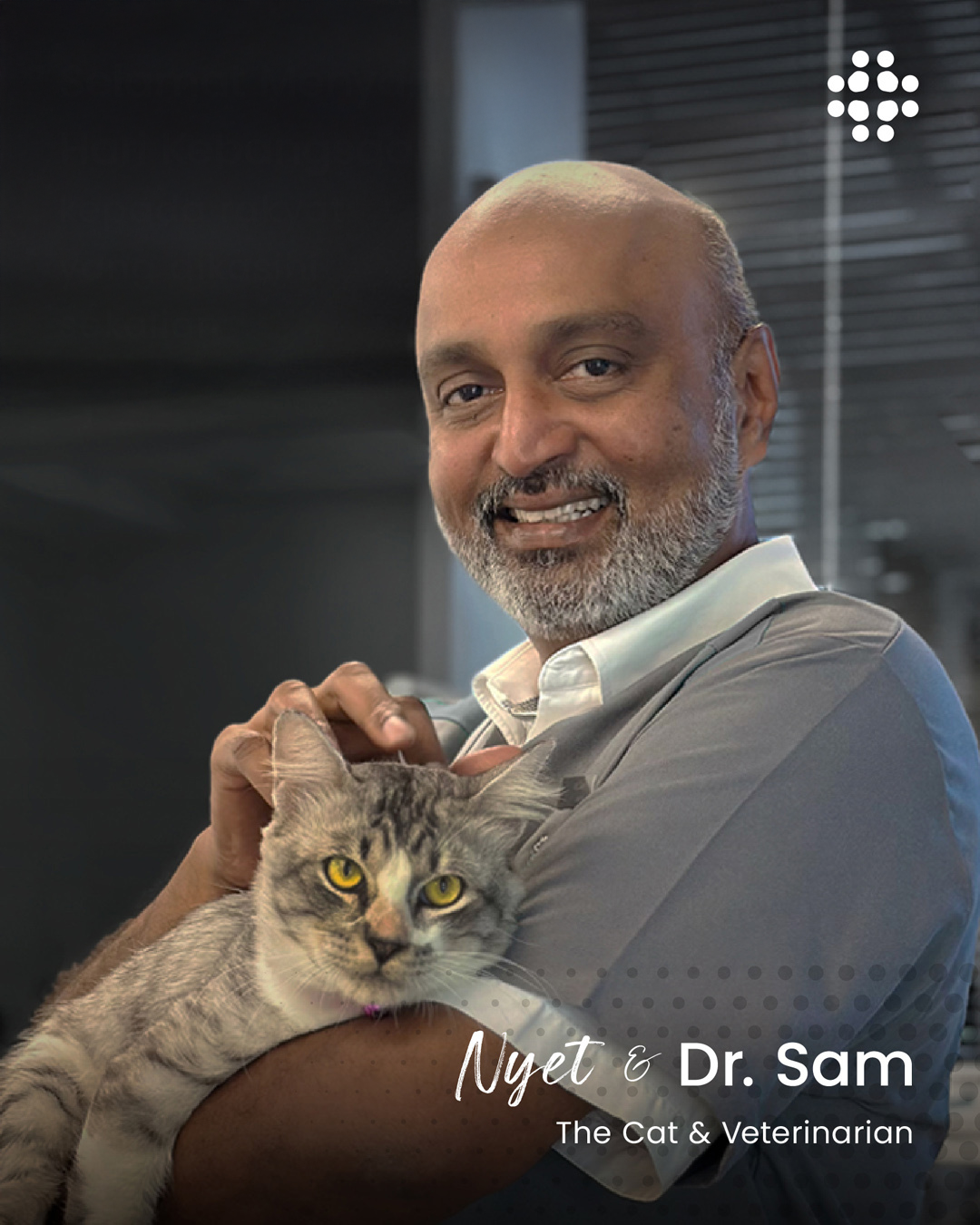

For Dr Sam Mohan Aruputham, becoming a veterinarian wasn’t always part of the plan. Today, he serves as Clinical Director at Windsor Animal Hospital, Penang, one of the few 24-hour veterinary hospitals in Malaysia, where he leads a team dedicated to saving lives around the clock.

We spoke with Dr Sam to learn how he found his calling in veterinary medicine, what it really takes to work in a high-pressure clinic environment, and how Malaysia’s pet care industry is evolving faster than ever before.

🐱Haven’t caught part 1 yet? Head over here and give it a read first!

1. First of all, what inspired you to choose veterinary medicine as your field of study?

Initially, I actually wanted to be an English teacher. Both my parents were English teachers, and I really admired the profession. After Form 6, I even applied to Universiti Malaya and NUS for English programmes, and I got accepted.

But when I told my father, he wasn’t happy. Even though he was proud to be a teacher, he also understood the frustrations of the profession and wanted something different for me.

So, using my Form 5 results, I applied to UPM for a Diploma in Animal Health. I did well in the diploma, and through UPM’s promotion pathway, top students could choose their degree. That’s how I ended up pursuing Veterinary Science, and I’ve never looked back since.

2. How was your journey in vet school, and what lessons did you take away from it?

Coming from school, where everything is structured and disciplined, university life was a complete shift. The biggest lesson was independence. Suddenly, you’re living on your own, responsible for everything, from your time and studies to your own well-being.

That transition taught me accountability and self-management. Looking back, that independence prepared me more for real life than any textbook ever could.

3. What led you to focus on small animal practice instead of other veterinary fields?

When I first graduated, people assumed vets knew everything. Back then, we were trained as generalists. You had to be ready for chickens, buffalo, small animals, anything.

My path wasn’t straightforward either. I wanted to be a horse vet, but that field was closed to overseas graduates. Then I tried working in a zoo, but with one vet for thousands of animals, it was emotionally overwhelming.

Farm work didn’t suit me either, so I joined the government service in parasitology. But the slow career progression pushed me toward the private sector, and later into sales.

Eventually, I found my place in clinical practice. And I learned that being a vet isn’t just about medical skill, it’s also about business sense, communication and resilience. Some vets are great surgeons, while others are great communicators. In the end, knowing your strengths and accepting your weaknesses is how you truly grow in this profession.

4. What are some misconceptions you face in small animal practice?

A big one is that because vets love animals, we should treat them with blood, sweat and tears, regardless of cost.

In small animal practice, the most common misunderstanding is about our fees. Many pet owners don’t realise that veterinary care involves real costs: specialised equipment, skilled staff, lab tests, and time.

Sometimes, owners rush in saying, “Do whatever you can, my cat is dying!” So we perform diagnostics (blood work, ultrasound, X-rays) to find out what’s wrong. But when they see the bill —RM200 for an X-ray or RM150 for blood tests —they question why it’s so expensive.

The truth is, our work is every bit as complex as human medicine. Loving animals doesn’t mean we can treat them for free.

5. What’s a typical day like at your clinic, and what kinds of cases do you see most often?

In a small clinic, you usually handle consultations, vaccinations and routine treatments; no lengthy hospitalisations or major surgeries. But at Windsor Animal Hospital, which runs 24 hours a day, it’s very different.

We work in shifts, and the night shift alone can see five to ten emergency cases like accidents, poisonings, critical illnesses and all things that need immediate care. The night vet stabilises the patients, and by morning, the surgery and ICU teams take over. We even have incubators and full-time monitoring, because clients now expect the same level of care they’d get in a human hospital.

There are only a handful of 24-hour vet hospitals in Malaysia, which are mostly in KL and Penang. Outside these areas, if a pet emergency happens at night, owners often have to wait until morning. Sadly, by then, it’s sometimes too late.

6. How do you cope with the emotional side of the job, especially when you can’t save every patient?

For many owners, their pets are family. So when we can’t save them, it hits hard for them and for us. It’s similar to paediatrics, where babies can’t explain what’s wrong, and neither can animals. When a patient dies in your care, it can be devastating.

That’s why I always tell young vets: it takes at least three years before you’re truly ready for clinical practice. You need time to build emotional strength.

Euthanasia, for example, is one of the hardest parts of the job. Some vets just can’t bring themselves to do it. Ultimately, it comes down to conviction. We all want to heal, but sometimes healing means letting go. That’s one of the toughest truths in this field.

7. The pet care industry in Malaysia seems to be growing quickly. What changes have you seen, and what does that mean for future vets?

The industry has grown tremendously, especially after COVID. More people adopted pets, and that created a surge in demand for veterinary services. Small animal clinics are thriving now, but at the same time, the livestock and public health sectors remain equally important.

Government roles, like those in the Department of Veterinary Services, might not seem glamorous, but they’re crucial. They ensure food safety, control diseases and protect public health. That’s where the One Health concept comes in: recognising that human, animal and environmental health are interconnected.

So whether you choose private practice, research or public service, there’s room for everyone. The veterinary field in Malaysia is expanding fast, and for passionate, resilient vets, the opportunities are endless.

Dr Sam’s story reminds us that being a veterinarian goes far beyond treating animals. It’s about resilience, compassion and finding meaning in both the joys and heartbreaks of the job.